Barriers and Opportunities for Distributed Energy Resources in Minnesota’s Municipal Utilities and Electric Cooperatives

by Gabriel Chan, Stephanie Lenhart, Lindsey Forsberg, Matthew Grimley, and Elizabeth Wilson

February 2019

This report summarizes our findings from a two-year research project to investigate the landscape of Minnesota’s municipal utilities and rural electric cooperatives. Our focus is on how these utilities are confronting new challenges and opportunities emerging from smaller-scale, often-more sustainable distributed energy resources, such as rooftop solar, community shared solar, LED light bulbs, controllable water heaters, and electric vehicles.

Executive summary

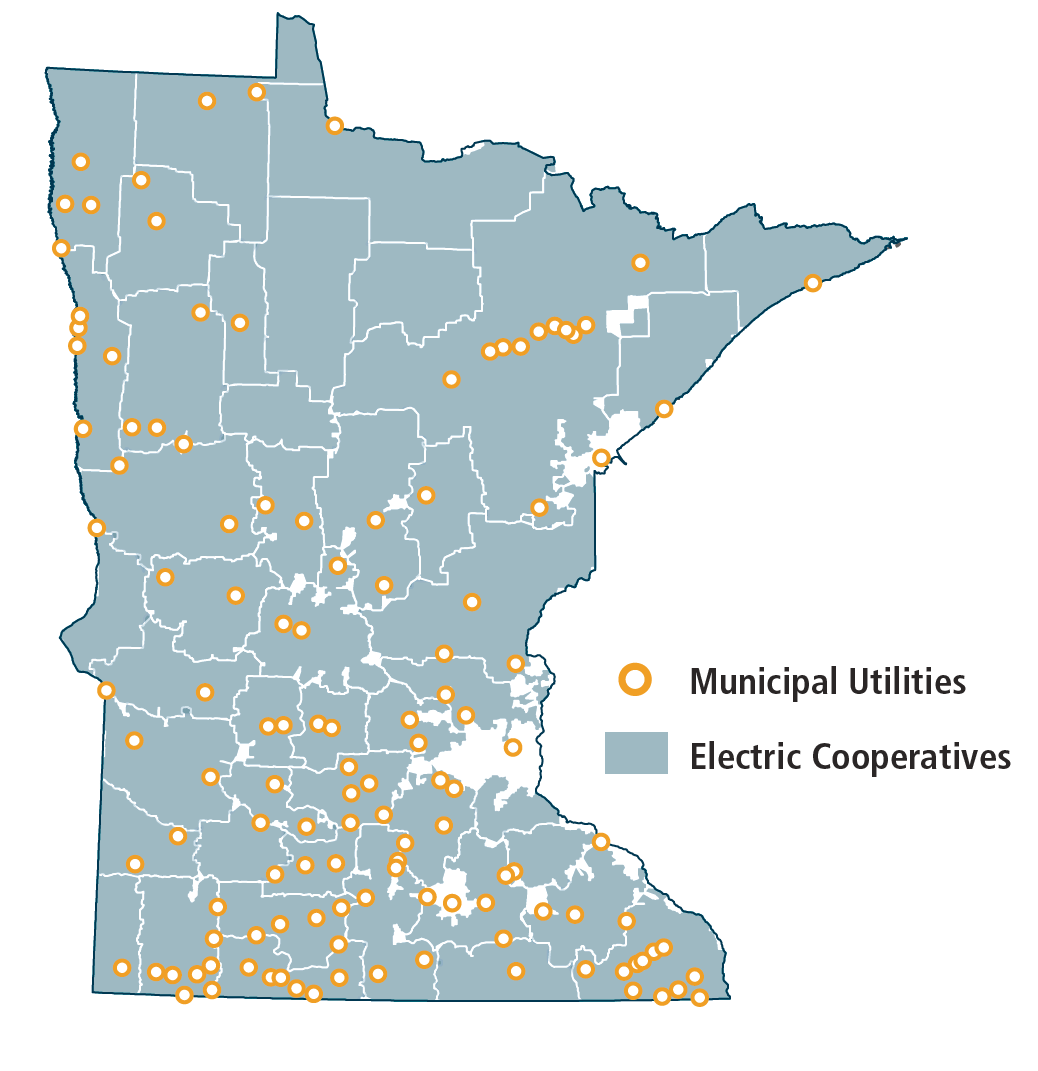

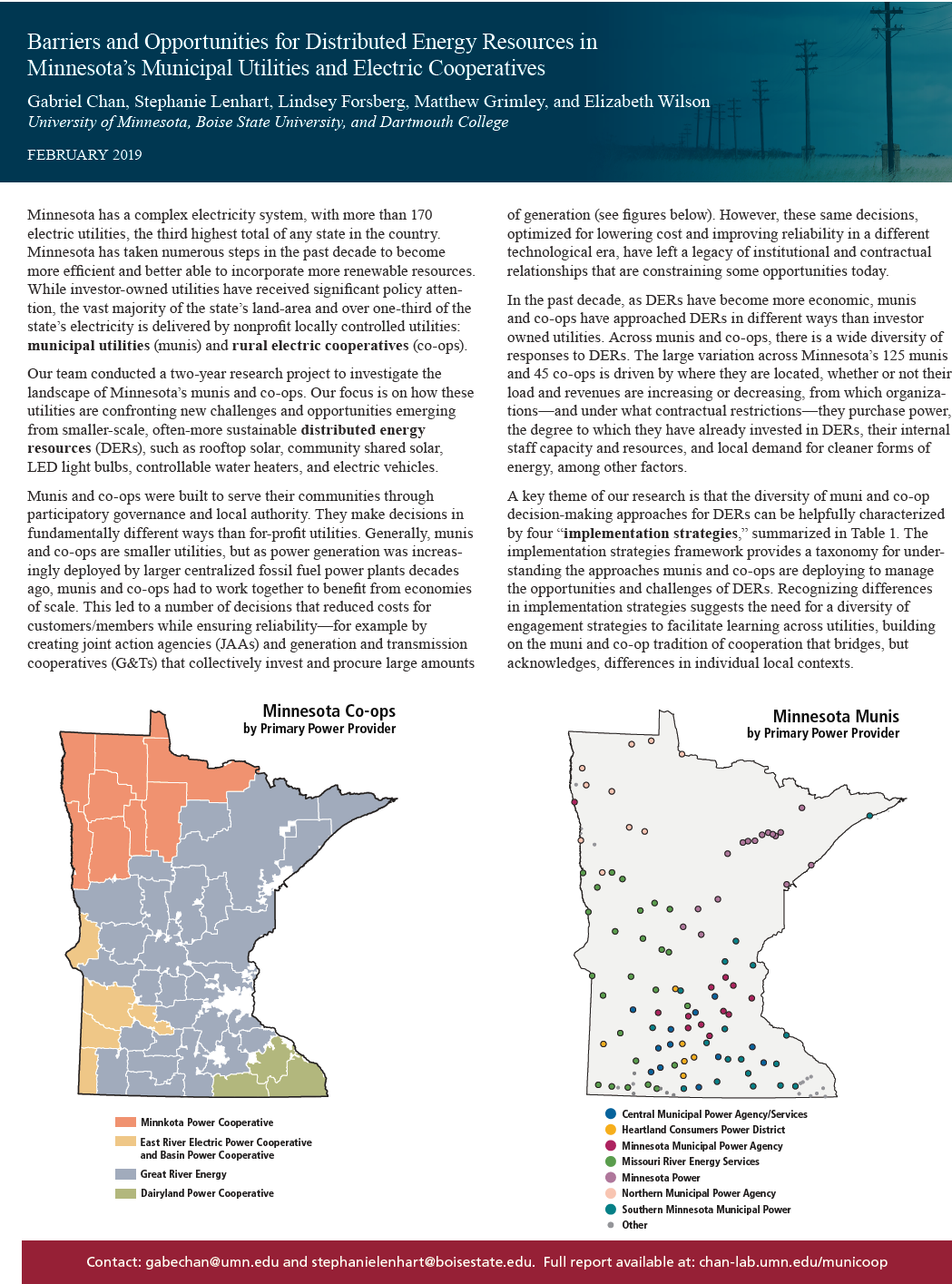

Minnesota has a complex electricity system, with more than 170 electric utilities, the third highest total of any state in the country. Minnesota has taken numerous steps in the past decade to become more efficient and better able to incorporate more renewable resources. While investor-owned utilities have received significant policy attention, the vast majority of the state’s land-area and over one-third of the state’s electricity is delivered by nonprofit, locally controlled utilities: municipal utilities (munis) and rural electric cooperatives (co-ops).

This report summarizes our findings from a two-year research project to investigate the landscape of Minnesota’s munis and co-ops. Our focus is on how these utilities are confronting new challenges and opportunities emerging from smaller-scale, often-more sustainable distributed energy resources (DERs), such as rooftop solar, community shared solar, LED light bulbs, controllable water heaters, and electric vehicles. Because munis and co-ops were built to serve their communities through participatory governance and local authority, they make decisions in fundamentally different ways than for-profit utilities. These decisions matter in the context of emerging technologies as actors across the state aim to create a fair and sustainable energy system for all members of the public.

As Minnesota’s energy system continues to evolve to meet new societal needs and incorporate new technologies, it is critical for local and state decision makers to understand the opportunities and challenges faced by munis and co-ops. Our project involves data analysis that paints a comprehensive picture of the electricity landscape in Minnesota’s munis and co-ops and interviews with over 50 executives from utilities across the state. This report aims to provide context for local and state decision makers, enabling them to respond to new internal and external pressures to find ways forward that best align with muni and co-op organizational goals, while also negotiating the possibilities for a more sustainable, fair, and empowering energy system.

Munis and co-ops were established over the past century to provide affordable and reliable electricity to Minnesota residents. In fact, many of these utilities (particularly co-ops) have their origin in the New Deal and the Progressive Era and are responsible for having brought the first electricity access to rural areas to support economic development and rural life.

Understanding the history of munis and co-ops utilities helps explain how they make decisions which guide today’s operations. It also highlights the opportunities and constraints of their decision making. Generally, munis and co-ops are smaller than investor-owned utilities, and as power generation was increasingly deployed by larger, more centralized fossil fuel power plants decades ago, munis and co-ops had to work together to benefit from economies of scale. This led to a number of decisions that reduced costs for customers/members while ensuring reliability—for example by creating joint action agencies and generation and transmission cooperatives that collectively invest and procure large amounts of generation. However, these same decisions, optimized for lowering cost and improving reliability in a different technological era, have left a legacy of institutional and contractual relationships that are constraining some opportunities today.

In the past decade, as DERs have become more economic, munis and co-ops have approached DERs in different ways than investor owned utilities. Across munis and co-ops, there is a wide diversity of responses to DERs. New pressures on electric utilities are highlighting existing differences. The large variation across Minnesota’s 125 munis and 45 co-ops is driven by where they are located, whether or not their load and revenues are increasing or decreasing, from which organizations—and under what contractual restrictions—they purchase power, the degree to which they have invested in their own local demand response, energy efficiency, and energy generation, their internal staff capacity and resources, and local demand for cleaner forms of energy, among other factors.

A key theme of our research, explored in Section 3, is that the diversity of muni and co-op decision-making approaches for DERs can be helpfully characterized by four “implementation strategies,” summarized in Figure ES.1. The implementation strategies framework provides a taxonomy for understanding the approaches munis and co-ops are deploying to manage the opportunities and challenges of DERs. Recognizing differences in implementation strategies suggests the need for a diversity of engagement strategies to facilitate learning across utilities, building on the muni and co-op tradition of cooperation that bridges, but acknowledges, differences in individual local contexts.

A second key theme of our research, explored in Section 4, is that munis and co-ops hold a unique position to be important agents in creating more sustainable, fair, and empowered local communities through their engagement with DERs. This potential is being shaped by multiple factors; we highlight three: (1) the potential re-structuring of the relationships between distribution utilities and their generation and transmission providers, (2) engagement of distribution utilities with local policy goals through participatory governance, and (3) addressing fairness across a utility’s customers/members and across distribution utilities that co-own generation resources.

Munis and co-ops rely on a complex set of relationships to deliver services: energy service providers, other distribution utilities, consultants, nonprofits, and local and state agencies all have a role. DERs are disrupting these institutional relationships and the rules and practices that munis and co-ops have relied on for decades. DERs expand the “solution space” for munis and co-ops to create community benefit. But DERs also create a need for policy, cooperation, and assistance.

Policy and engagement efforts with munis and co-ops should target the appropriate scale for intervention, compliance, and participation—from the state-level, to the utility level (the generation and transmission level or the distribution level), to the customer/member or community level. The findings of our report inform a set of five key takeaways that can inform program design and policy options at these different scales (detailed in Section 5):

The diversity of munis and co-ops creates an opportunity for learning across utilities, experimentation, and more effective collaboration. The common shared principles of munis and co-ops can create common ground for exchanges even when implementation strategies vary.

Long-term power supply contracts present a constraint for many munis and co-ops. Understanding these constraints and potential for change may require technical assistance or other support.

As demographics and communication technologies continue to change, munis and co-ops are likely to see increasing pressure for information sharing, transparent decision making, structures for representation, and modes of participation.

DERs bring notions of fairness to the fore, and any internal or external intervention should engage with stakeholders to understand the realities and perceptions of fairness across scales (between customers/members, utilities, and wholesale market participants).

Many munis and co-ops face limits to their internal capacity and may require new financing, risk reduction, and joint ownership opportunities before taking a more active role in incorporating DERs to their utility system.